The Citadel Man Who Became A Legend

By Rose Marie Godley, Citadel News Director

This article originally appeared in Alumni News of The Citadel – Winter 1972-1973. It is posted here in its entirety with the permission of the Citadel Alumni Association.

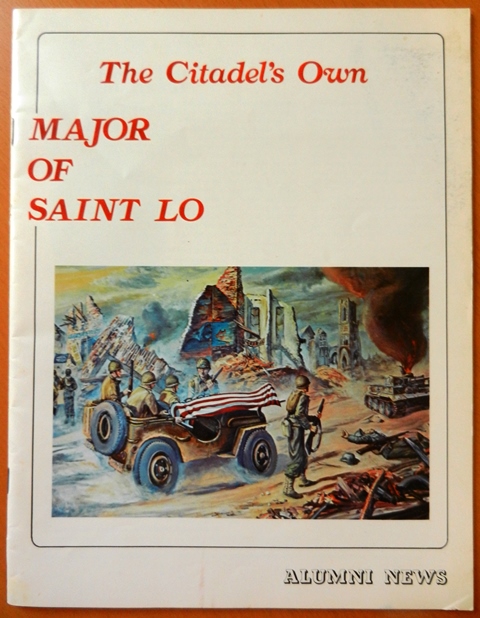

Front cover of Alumni News of The Citadel – Winter 1972 -1973

The earth shuddered as the Germans began their heavy counterattack. Maj. Thomas Dry Howie, ’29, warned his men, “Keep down!” And reassured them, “We’re getting out of here soon. We’ll get to Saint Lo yet!”

The Germans knew the value of holding Saint Lo with its vital network of roads. Only after the town was taken could American armor maneuver in the plains beyond to achieve the longed-for breakout.

Above the noise Howie explained his position over the battle phone to Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt, the commanding general.

“The Second can’t make it,” he yelled into the phone. “‘They’re too cut up. They’re exhausted. Yes – we can do it. We’re in better shape. Yes – if we jump off now. Okay.” Howie smiled. “See you in Saint Lo.”

Howie called for his map and gave orders for attack on Saint Lo – so close.

Then came a sudden German mortar barrage.

“Before taking cover in one of two foxholes which we were using, Major Howie turned to take a last look to be sure all of his men had their heads down,” said Capt. William H. Putenny, Howie’s executive officer.

“Without warning one of their mortar shells hit a few yards away and exploded. A fragment struck the Major in the back and apparently pierced his lung. ‘My God, I’m hit,’ he murmured, and I saw he was bleeding at the mouth. As he fell, I caught him.”

Capt. Darrell R. Spicer, commander, Headquarters Company, First Battalion, 116th Infantry. wounded in the burst recalls, “Word was spread immediately and even though the men of the battalion were hardened veterans of war, you could see tears in their eyes as they heard of the death of their beloved Major.”

Howie’s words, “See you in Saint Lo!” became the battle cry.

When General Gerhardt organized a task force to smash into the city, he remembered Tom’s last wish.

Hal Boyle, war correspondent with the 116th, wrote, “By the General’s order, Tom’s body, still clad in full combat gear was placed in an ambulance in the task force column. I looked in and saw him.”

Boyle followed, “Amid the thunder of guns, the armored column – bearing the dead hero – fought toward Saint Lo. When the ambulance was needed for the wounded, Tom, lying on a stretcher, was transferred to a leading jeep.

“The column trundled on. It smashed through the last ring of German defenders and entered the city which was a mass of flaming ruins.”

According to Boyle, “Tom’s men quickly lifted their dead major from the jeep and ran through enemy sniping to a nearby shell-torn church. There they placed him atop the rubble of the church wall and went back into battle. They had won for him the last goal of his life – he was ‘the first into Saint Lo.”‘

The body of “The Major of Saint Lo” lay in state for three days on the rubble of St. Croix while his men – strong men calloused to death – paid final honor with tears and unspoken tributes, reserved for men dear to men.

Above, the flag draped body of Major Thomas D. Howie rests atop the rubble of a wall of St. Croix cathedral in Saint Lo. Below left, a task force from the 29th Division moves down the main street of Saint Lo mopping up enemy resistance. Below right, a military convoy moves through the ruins of Saint Lo shortly after the city was taken.

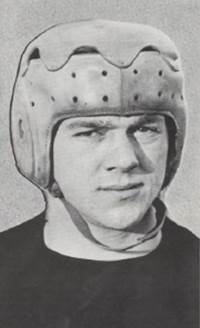

The Citadel annual, the Sphinx, put it this way: “Tom is right much hell… He was a terror on the gridiron. Yes a terror.”

Teammate T. E. Wilson, ’31, said, “Tom charged into the opposing line sounding like a wild rebel, or an Indian on the warpath, leading the blocking. He not only sounded like he was on the warpath, he blocked like it. It instilled confidence in the rest of us.”

“Tom liked people, and people liked him,” pleasantly affirms Col. C. F. Myers, ’14, who was Tom’s freshman math teacher at The Citadel. “Throughout his years at The Citadel he stopped by my office frequently between classes to chat. And he was such a bright student – undertook his studies with real application.”

This application was part of Tom Howie – student, athlete, teacher, coach, and battle commander.

If Col. D. S. “Red” McAlister, ’24, hadn’t learned that while Tom was a cadet, he found out shortly after Howie graduated. McAlister, who had captained The Citadel baseball team in 1924 and then joined the faculty, played on the baseball team in his hometown, Iva, S. C. one summer a couple of years after Howie had graduated.

“The team was mostly teenagers. I got involved through my younger brother,” says McAlister. “They had me pitching.”

“I went along with the team to Abbeville where we were playing the ‘town team.’ They had a little age and experience on us. Tom was spending some time in Abbeville, and darned if he wasn’t on the team!”

A smiling, sparkling Tom came up and welcomed Colonel McAlister, “Then he proceeded to explain the game of baseball to me, as if I’d never chunked a ball or held a bat!”

Tom had two strikes his first turn at bat. McAlister curved a ball, Tom struck, and out he was.

“He was quite amazed that I could throw a curve and pretty angry with himself. But you couldn’t fool Tom with the same trick twice. The next time I tried it, he abso lutely lost that ball!”

There were many facets to the jeweled character of Tom Howie. He was a humble, dependable, well disciplined man, a man of principles. He was willing to stand up for those principles, and fight for them if neces sary. Col. J. G. Harrison, ’23, an English professor at The Citadel, observed this trait of Tom’s character in 1928.

That year the conditions in the mess hall were reportedly poor – stale bread for toast, flies in the syrup.

“Howie believed in discipline,” stated Colonel Harrison, “but knew there were times when, after all other means failed, drastic measures must be taken.”

He and several other cadets led the entire Corps of Cadets in a hunger strike until mess hall conditions were greatly improved.

“It was all done legally with no rules broken,” affirms Colonel Harrison.

Tom was versatile. He was chairman of the Round Table. He was elected by his fellows to the Honor Committee. Tom was a playful, social being. He was chairman of the Senior Hop. He was active in half dozen other clubs and societies and captain of the baseball team. “Although he never tried to dominate, others looked to him for leadership,” recalls Tom Sills.

Howie didn’t stay behind and urge others into the fray. He was the first through the line, or in class work. In Normandy, he was at the front with his men – showing them how to do it. When he was stationed in England, he held an administrative post but asked to be released in time to lead a battalion in the June 6, 1944 Normandy invasion.

His men admiringly complained that Major Howie did all the fighting. He dashed ahead of them. Several times he silenced German machine gun nests, and did it singlehandedly.

The combination of training, character, experience, personality, and supreme leadership blended in this one man to provide the intensive drive with which the Third Battalion, 116th Infantry, 29th Division accomplished its goals.

Synthesized in him was the free-wheeling flexibility of a small-town South Carolina heritage and the discipline of a universal lifestyle found in the military.

Howie went from The Citadel to the classrooms and playing fields of Staunton Military Academy in Staunton, Va. where, as a faculty member and alumni secretary, he displayed even more of the maturity and leadership that characterized his undergraduate life in Charleston. A contemporary from Staunton, Len Taylor, testifies: “He was the type of man you wanted to call your friend, even though you had met him but a few times. His personality was such that to find its equal is almost an impossibility.”

Howie taught English, and in that first year at Staunton he met the woman he was going to marry, a Staunton girl, Elizabeth “Tee” Payne. It was a blind date.

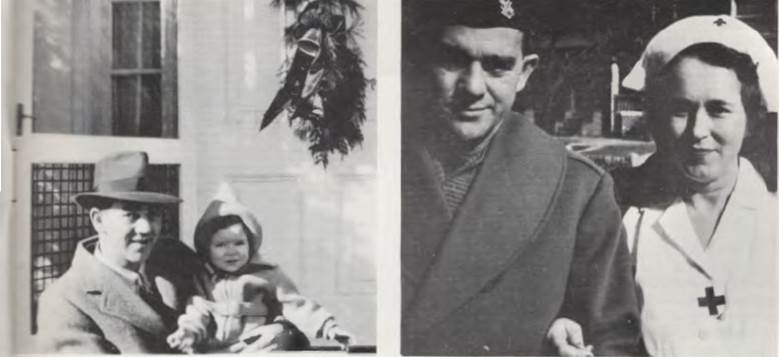

“I was surprised to find him so attractive,” she said. Tom asked her out again the next night. Miss Payne, though romantically involved with another man, a medical student, continued to see Tom Howie, and “By summer we found ourselves very much in love.” They were married in 1932. Their daughter, Sally, was born in 1938.

Left, Tom Howie with daughter Sally at Staunton. Right, Major and Mrs. Howie, 1941. Below, the Mayor of Saint Lo, Mrs. Howie, and Sally at Major Howie’s grave, 1969. [Normandy American Cemetery]

It’s a long way to Tipperary, and a long way from Charleston, S.C. to Saint Lo in France. But the capacity for leadership, the ability to inspire others to extraordi nary heroism was the same in 1944 when Major Howie led his troops advancing through Normandy as it was at The Citadel when Cadet Howie led his teammates on the football field.

This was especially true on Homecoming Day, 1928. The outlook was gloomy because year in, year out the Bulldog had been underdog to the Clemson Tiger.

But as the Clemson-Citadel game was about to begin, the cadets suffered an extra handicap. Their star halfback, Tom Howie, 150 pounds of muscle, speed, intelligence, and coordination, was absent, delayed by a scholarly errand.

Tom was in Columbia, taking a Rhodes Scholarship examination. He expected to be back in Charleston in time to suit-up for the game. But the test was postponed three hours, till noon that Saturday, and the game began at 2 p.m., 115 miles away.

Ephie Seabrook, The Citadel’s assistant coach, drove Tom Howie to Columbia in his new Studebaker. “My hope was to be with Tom as he finished the exams that Saturday morning and break the speed limit getting him back to Charleston,” said Coach Seabrook. “I was panic stricken when they told us the Rhodes examination wouldn’t begin until 12 o’clock.”

But Howie didn’t panic. In his easy, happy manner he told Coach Seabrook, “Don’t worry, Coach. We’ll get back to Charleston in time for the game.”

Cadet Howie whipped through the examination in record time. At 12:35 Seabrook and his valuable passenger were speeding toward The Citadel and the big game. Just before 2 o’clock, The Citadel team was downcast. In his pregame dressing room talk, Head Coach Carl Prause was eloquent, but he was aware of a spirit of dejection in the players. He knew that without the missing sparkplug, Tom Howie, chances of beating Clemson were slim.

As the players lined up to run onto the field, Ephie Seabrook’s car arrived in a cloud of dust. Tom was already in uniform – dressing on the hectic ride from Columbia to Charleston. He was ready to play football.

Col. John Rogers who was a spectator at the dressing room door said, “A miraculous change came over our team when they saw Howie. In unison they produced a tremendous yell. All of them who could ran to him and grabbed him like a long-lost brother. I figured right then we would beat Clemson that day.”

Clemson had an All-American center, O. K. Pressley, a stalwart barrier in the Tiger line.

In the first running play of the game, Tom Howie carried the ball and ran directly into and over Pressley, for 10 yards and a first down.

A Citadel teammate, Howard Duvall, ’29, declares, “To run like that against Clemson set our team on fire. ” The score was 7 to 6 in favor of Clemson in the final quarter, when Sam Wideman, ’29, of the Bulldogs blocked a Tiger punt, helping The Citadel to score a touchdown, and a 12 to 7 upset over Clemson.

Did Tom Howie rush through his Rhodes Scholarship exam in too much haste? Perhaps so, and perhaps not. He missed going to Oxford by a fraction of a percentage. But he was the hero of the day at Homecoming, 1928!

That was the kind of man he was. He inspired those around him to greater achievement. His life – according to those who knew him in his hometown of Abbeville, S. C., at The Citadel, at Staunton Military Academy where he taught in the 1930’s, and in World War II – provides a lesson in personal leadership, of manly character, and example that young men should heed in war and peace.

His personality bridged the gap between ideals of a free people committed to peaceful civilian pursuits and the necessity of inspiring men to defend those ideals in battle.

“He was such a wonderful fellow, so full of enthusiasm,” states Thomas Sills, a Citadel classmate. “If we had been using the word ‘charismatic’ back in those days, it would have applied as much to Tom as it did to John F. Kennedy.”

Poets and composers might well be able to write themes about Tom Howie – the example he set in classrooms, clubs, discussion groups, on the playing fields, in his life in Virginia with his wife and his family, and in the final culmination of his career when he starred in the role of heroic warrior.

Such a composition would tell of Tom’s magnetic personality, his wry sense of humor, his intellect.

Col. H. S. “Tip” McGillivray, who taught Tom English at The Citadel looked on him as his best student. But the Colonel did not approve of intercollegiate athletics and grumbled that sports took time from academics.

One day Tip was calling the roll, and Howie didn’t answer.

“Does anyone know where Mr. Howie is today?” asked Tip.

A cadet spoke up. “He is away with the football team. We play Furman tomorrow.”

Tip was flabbergasted. Incredulously and with pained disappointment showing on his countenance, he asked, “You mean Mr. Howie plays football”

Tip was assured that Howie played ball and played it well.

“He was about five feet, ten, and weighed 150 pounds – wet,” said Wideman, a tackle on the Bulldog team.

… a father to me …

Tom Howie’s Brother Reminisces

What was Tom Howie like to his younger brother?

Franklin Howie of Abbeville tagged along after his brother Tom when they were youngsters. “He was my idol,” writes Franklin Howie. “I turned to him for help, for a buck, or whatever I needed at the moment. Had it not been for him I am sure I would have been a high school dropout.”

When Tom Howie was teaching at Staunton, he arranged for his younger brother to join him there as a student, and Frank Howie played football at Staunton.

In those early Abbeville years Tom Howie, as a little boy, displayed the magnetism that attracted people to him. Next door to the Howie home was a large boarding house where men stayed when they were in town, and they made Tom something of a pet, a mascot. He made himself useful at the boarding house, helping a black man shine shoes. Tom considered the shoeshine and boarding house handyman his best friend, and he learned the trade by watching the veteran pop the shining cloth with a rhythmic staccato series of movements that was as entertaining as it was efficacious in shining shoes. The black man showed Tom how to make a shoeshine box of his own. The box is now in the possession of the Howie family in Abbeville.

In high school Tom was still a worker – a printer’s devil for the Abbeville Press and Banner. During the summer he worked as a laborer for Abbeville Mills – on the “outside gang” that kept the grounds and tended the mill and village, and he played baseball for the mill team in the textile league.

Frank Howie learned of another striking tribute to his older brother. A soldier in Major Howie’s outfit was questioned by his own father later about newspaper accounts of Howie’s leadership and heroism. “Was the Major of Saint Lo as great as the newspapers made him out to be?” the father asked. The young veteran replied, “Dad, he was more of a father to me overseas than you were when I was here.”

General Omar N. Bradley and Mrs. Howie at the dedication

of a monument to Major Howie in Saint Lo, June 1969.

Life was happy in Staunton where Tom was a brilliant teacher and active in sports. In the eight years he was head football coach, his teams won four military school state championships. Sports writers competed to cover his games.

“He was one of the greatest guys that ever lived,” states Paul Robey, a member of one of Howie’s teams at Staunton.

“I’ll always remember our pregame talks. He used to settle our nerves with just a few words.”

War loomed on the horizon. Howie was a second lieutenant in the 116th Infantry, Virginia National Guard, when the unit was called for intensive training in 1941. The great story of Tom Howie, the legend of the Major of Saint Lo, then began.

“Tom Howie rests in Valhalla.”- Gen. Charles P. Summerall

For 41 days Howie’s Third Battalion fought continuously through the bloody hedgerows of Normandy, capturing and recapturing field, ditch, sunken road. Howie’s unit was still three miles from Saint Lo. The fighting was toe to toe, firing at pointblank range, grenades across narrow fields.

Howie believed his men had earned the right to be first in Saint Lo.

Then orders to relieve Col. Sidney Bigham’s Second Battalion seemed to prevent Howie’s wish from being fulfilled. He’d been given the toughest assignment in the division – to drive through the Martinville line, which had held for days.

With his experience, leadership ability, drive, Tom led his men in the accomplishment of this feat in an hour and a half, rescuing the cut-off decimated ranks of the Second Battalion at La Madeleine.

The battalion was now a mile from its objective.

The death of Thomas Dry Howie, “The Major of Saint Lo,” as his battalion was about to seize the strategic town held by the Germans served only to spur his loyal men to unusual heights of energy and valor. They fought with fury and captured Saint Lo, clearing the way for the

BADGES OF BRAVERY FOR SERVICE BEYOND THE CALL

Thomas Dry Howie, a hero’s hero, perished under fire so early in his spectacular combat career that he might well have received no medals. That would have been no travesty because Howie’s heroism and poignant courage became enshrined in the hearts of patriots round the world.

That he performed above and beyond the call of duty, however, was recognized formally by grateful governments. He was awarded the Silver Star Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, the Purple Heart, the French Legion of Honor, and the French Fourragere, and he qualified also for the cherished Combat Infantry Badge.

116th and the 29th Division of the American Army to continue its march toward the Rhine, and ultimate victory for the Allies.

At the dedication of a granite marker in Abbeville commemorating Howie’s heroic career, the late General Charles P. Summerall, former president of The Citadel, said, “Tom Howie rests in Valhalla, but that indelible something so distinctly inscribed upon ‘his boys’ can never die.”

The National Guard Armories in Greenwood, S. C., and Staunton, Va., now bear Tom’s name.

On the campus of Staunton, a bust of “The Major of Saint Lo” has been handsomely installed. At its unveiling high government officials, military personnel, and representatives of the French government and military were present.

Since 1945 the “Howie Rifles,” an honor society at Staunton Military Academy, has required the high standards of its members which Tom sought to instill in young men.

One of the largest Dutch bell installations in the Western Hemisphere is contained in the Thomas Dry Howie Carillon Tower at The Citadel. It was erected by one of Tom’s classmates, Robert Hugh Daniel, and his brother, the late Charles E. Daniel, also a Citadel alumnus.

In The Citadel’s Memorial Library there is a huge mural of “The Major of Saint Lo,” painted by David Humphreys Miller. It is reproduced on the cover of this magazine.

Left, Hugh (’29) and Charles (’18) Daniel, Governor James F. Byrnes, and General Mark W. Clark at the dedication of the Thomas Dry Howie Carillon Tower, Dec. 1954. Right, monument to “The Major of Saint Lo” on the Staunton Military Academy campus.

A picture of the mural was recently hung in the headquarters of the Saint Lo Brigade. In 1969 the Department of the Army awarded that distinctive designation to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Armored Division in honor of that brigade’s “loyal and faithful service” in ending the hedgerow fighting in Normandy.

During the celebration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the liberation of France in 1969, Mrs. Howie, Sally, and her husband were guests of the city of Saint Lo where a memorial was dedicated to Major Howie. The ceremony was attended by a hundred thousand people, troops from all Allied Nations, dignitaries from France, the American Ambassador and top World War II generals.

Mrs. Howie, who has continued to maintain her residence in Staunton, is frequently called upon to speak to groups interested in learning more about her valiant husband. She recalls the final letter her husband wrote to her and her daughter in his lighted dugout on a battlefield in France: “I have no physical reason for thinking so, but I’ve always felt that your prayers would be answered and that we’d have a grand reunion some fine day.”

Sally is married to T. Carlyle Lea, Jr., an attorney in Culpepper, Va. They have two sons and two daughters.

To them Tom left a valuable heritage. In his too-brief career his magnetism drew men of all walks of life. He was a man of tremendous integrity, high intellect, strong loyalty, unlimited courage, full humility, complete dependability, sound judgment, and understanding tact.

“Dead in France – Deathless in Fame”

/RMG

Please show your appreciation and support for The Citadel Memorial Europe with a “Like” or a “Follow“. Buttons are located at the top of this page in the right-hand sidebar.

This issue of Alumni News was privately acquired and donated to The Citadel Memorial Europe specifically for this purpose. The CAA does not have a copy of this issue and has gratefully allowed posting of the article in its entirety on the memorial website. Please contact us you would like to receive a pdf copy of the scanned original article.

About The Citadel Memorial Europe

Our not-for-profit, all volunteer Foundation, headquartered in The Netherlands, exists to:

- Respectfully honor and remember the Citadel Men who died in Europe or North Africa while in the service of their country

- Research, collect, and share their stories with an extra focus on their time at The Citadel

- Raise awareness and knowledge about them within The Citadel community

- Recognize and connect with the people of Europe who have adopted the graves and names of the Citadel Men interred in overseas military cemeteries

- Raise awareness with other memorial groups of the bond between these men and The Citadel

My father 1st Lt. George E. Bryan, (Clemson 1937) an Allendale, SC native, served under Major Howie. He happened to be standing next to Major Howie when Major Howie was hit, during the battle for St. Lo. and subsequently died. My father was interviewed and quoted in several SC newspapers about Major Howie’s leadership qualities, and his being loved and admired by his men serving under him. I believe my father was serving under Howie before and during D-Day where he was in one of the first waves onto Omaha Beach, then continued serving under Howie throughout the heavy hedgerow battles as they fought their way into St Lo. Unfortunately I lost all of those articles in a house fire during 1996. My father and mother were invited to join with the family on the podium, at the dedication of the Carillon Tower when the dedication happened during Dec of 1954. I remember the day that happened, but I did not attend the event. My dad survived the war and passed away during 1993. My father told me how he heard the incoming, and ducked for cover, but Maj Howie kept standing, and was hit. He heard Major Howie say, “My God, Ive been hit” and knew that it was a severe wound.

George E. Bryan, Jr.